Predicting Breathing Rates using Smart Watch Data¶

by Joe Ganser

Abstract¶

This research was the product of a data driven healthcare hackathon I participated sponsored by Accenture and the School of AI. I was the team leader, and our team came in first place for the NY division. Here we use blood oxygen and electrocardiogram data to predict the rate at which people breath. It turns out, this data can be extracted from a smart watch. Using this data, we could predict a persons respiratory rate with 90% accuracy.

Our official presentation title

I. Introducing the problem¶

Background information & Context

Electrocardiogram (ECG) data and photoplethysmogram (PPG) data are extremely useful in healthcare. They are used to assist in diagnostic methods for a wide array of diseases. ECG measures cardiac properties and PPG data measures blood oxygen levels using optical instruments. (1,2)

Both ECG and PPG data can be extracted from a smart watch at the same level of accuracy and precisions of machines found in hospitals. ECG and PPG can be combined to predict breathing rate, and using the combination of all this data (3,4,5).

The data used for this analysis was not actually collected from a smart watch, but smart watches have the capability to collect the same data. The data used in this analysis was from 53 patients in intensive care, where their ECG, PPG and breathing rates were measured. (4,5,6)

Goals of the analysis

The goal was to use supervised machine learning techniques to predict a persons breathing rate using real time, continuous PPG and ECG data.

In conjunction, it was also our goal to investigate the feasibility of using this type of data for enhancing diagnostic processes in healthcare. We ended by speculating on the market evolution of technology that integrates these methods.

II. Data Structure & Feature Engineering¶

How the data was originally harvested

The data used for this analysis was time series recorded from 53 ICU patients, in age ranges between 19-84. Both male and female patients were present. They were recorded using hospital based ECG and PPG devices, and a breathing apparatus. Continuous measurements for each patient were made across apporximately 8 minutes (6).

The original data's structure: ECG, PPG & pulminory

The data was aggregated from two fundamental sources - one which was collected at 1Hz and the other at 125Hz. These were then joined in a left outer manor. Some of the key features were;

- Respiratory rate (the supervised learning target)

- Pulse

- Blood oxygen level

- Pleth (pulmonary data)

- V (voltage)

- AVR

- II

The 1Hz data looked like this;

| Time (s) | HR | PULSE | SpO2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 93 | 92 | 96 |

| 1 | 92 | 92 | 96 |

| 2 | 92 | 92 | 96 |

| 3 | 92 | 93 | 96 |

| 4 | 92 | 93 | 96 |

The 125Hz data looked like this;

| Time (s) | RESP | PLETH | II | V | AVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.25806 | 0.59531 | -0.058594 | 0.721569 | 0.859379 |

| 0.008 | 0.26393 | 0.59042 | -0.029297 | 0.69608 | 0.69531 |

| 0.016 | 0.269790 | 0.58358 | 0.179690 | 0.7 | 0.45508 |

| 0.024 | 0.27566 | 0.57771 | 0.84375 | 0.32941 | 0.041016 |

| 0.032 | 0.2825 | 0.57283 | 1.3184 | 0.078431 | -0.099609 |

After combining with left outer join, we got;

| Time (s) | RESP | PLETH | V | AVR | II | HR | PULSE | SpO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.25806 | 0.59531 | 0.721569 | 0.859379 | -0.0585944 | 93 | 92 | 96 |

| 0.008 | 0.26393 | 0.59042 | 0.69608 | 0.69531 | -0.029297 | 93 | 92 | 96 |

| 0.016 | 0.269790 | 0.58358 | 0.7 | 0.45508 | 0.17969 | 93 | 92 | 96 |

| 0.024 | 0.27566 | 0.57771 | 0.32941 | 0.041016 | 0.84375 | 93 | 92 | 96 |

| 0.032 | 0.2825 | 0.57283 | 0.078431 | -0.099609 | 1.3184 | 93 | 92 | 96 |

For each person in the study, this amounted to about 60,000 rows. When all 53 people were combined, we were left with approximately 2.7 million rows (about 1.2Gb of data.)

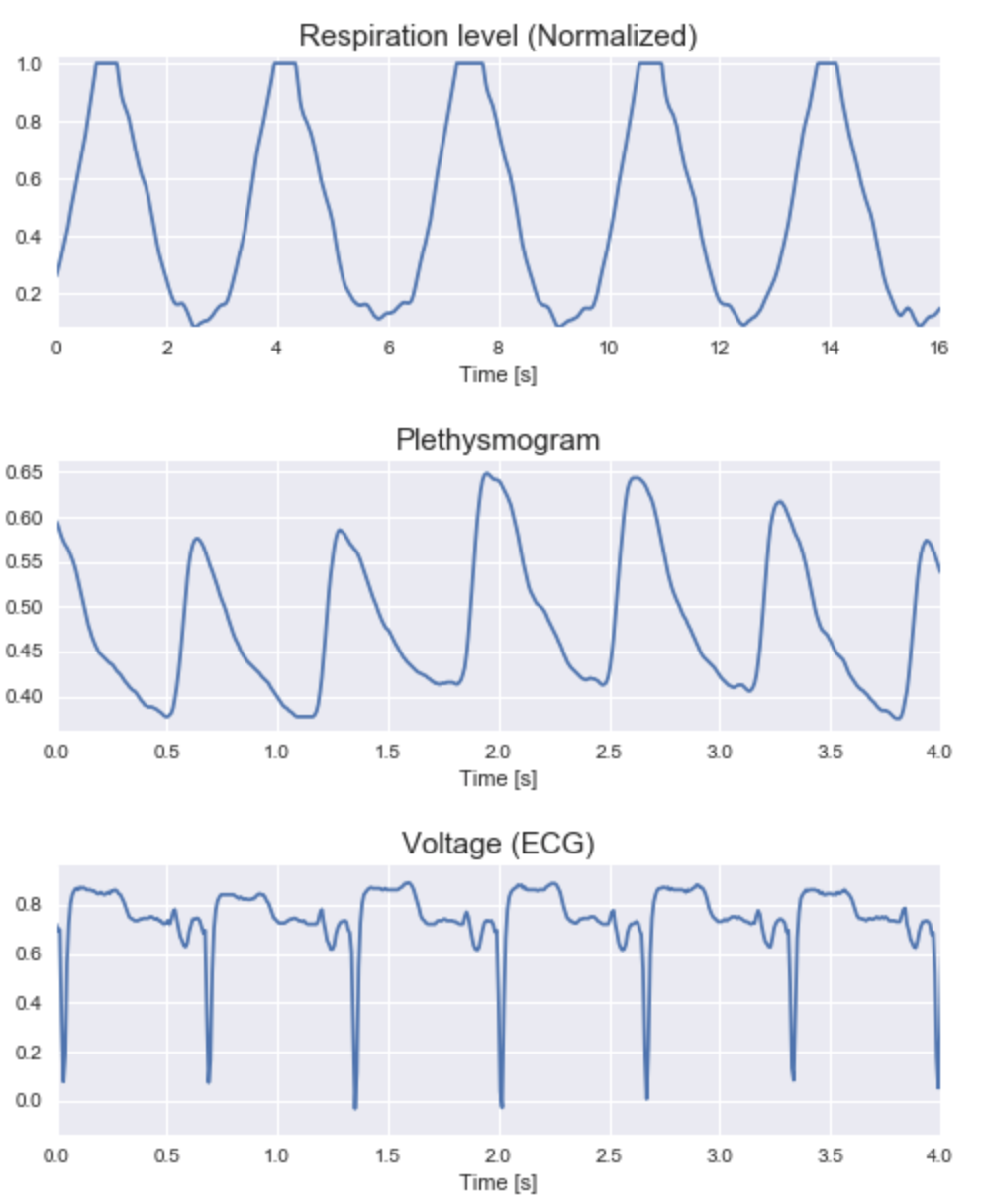

Visualizing the fundamental data

The data was fundamentally time series based. Here are a few snapshots of some of the key features;

Feature engineering

Considering the aggregation of the data from 125Hz, the values of the metrics varied quite a bit in each second. Thus, summary statistics of the 125 values collected each second could be engineered into features. Specifically, these features were;

- Max value

- Min value

- Mean value

- Kurtosis value

- Skew value

(Over the distribution of the 125 measurements made each second). To create these features, a function was created.

from scipy.stats import kurtosis,skew

def make_features(frame):

frame.fillna(numerics.mean(),inplace=True)

Hz_125_cols = [' RESP', ' PLETH', ' V', ' AVR', ' II']

Min = frame[Hz_125_cols+['sec']].groupby('sec').min()

Min.columns = [i+'_Min' for i in Min.columns]

Max = frame[Hz_125_cols+['sec']].groupby('sec').max()

Max.columns = [i+'_Max' for i in Max.columns]

Mean = frame[Hz_125_cols+['sec']].groupby('sec').mean()

Mean.columns = Mean.columns = [i+'_Mean' for i in Mean.columns]

Kurt = frame[Hz_125_cols+['sec']].groupby('sec').agg(lambda x: kurtosis(x))

Kurt.columns = [i+'_Kurt' for i in Kurt.columns]

Skw = frame[Hz_125_cols+['sec']].groupby('sec').agg(lambda x: skew(x))

Skw.columns = [i+'_Skw' for i in Skw.columns]

summary_frames = [Min,Max,Mean,Kurt,Skw]

one_sec_summary = pd.concat(summary_frames,axis=1).reset_index()

frame = frame.merge(one_sec_summary,on='sec',how='outer')

return frame

| Time (s) | RESP | PLETH | V | AVR | II | HR | PULSE | SpO2 | RESP_Min | PLETH_Min | V_Min | AVR_Min | II_Min | RESP_Max | PLETH_Max | V_Max | AVR_Max | II_Max | RESP_Mean | PLETH_Mean | V_Mean | AVR_Mean | II_Mean | RESP_Kurt | PLETH_Kurt | V_Kurt | AVR_Kurt | II_Kurt | RESP_Skw | PLETH_Skw | V_Skw | AVR_Skw | II_Skw |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.25806 | 0.59531 | 0.72157 | 0.85938 | -0.05859 | 93 | 92 | 96 | 0.25806 | 0.37732 | 0.07451 | -0.09961 | -0.21484 | 1.0 | 0.59531 | 0.87059 | 1.0254 | 1.3438 | 0.70822 | 0.46446 | 0.75551 | 0.81947 | -0.02431 | -1.40052 | -1.08775 | 10.3465 | 13.15985 | 13.94906 | -0.24258 | 0.48232 | -3.05758 | -3.3357 | 3.5823 |

| 0.008 | 0.26393 | 0.59042 | 0.69608 | 0.69531 | -0.0293 | 93 | 92 | 96 | 0.25806 | 0.37732 | 0.07451 | -0.09961 | -0.21484 | 1.0 | 0.59531 | 0.87059 | 1.0254 | 1.3438 | 0.70822 | 0.46446 | 0.75551 | 0.81947 | -0.02431 | -1.40052 | -1.08775 | 10.3465 | 13.15985 | 13.94906 | -0.24258 | 0.48232 | -3.05758 | -3.3357 | 3.5823 |

| 0.016 | 0.26979 | 0.58358 | 0.7 | 0.45508 | 0.17969 | 93 | 92 | 96 | 0.25806 | 0.37732 | 0.07451 | -0.09961 | -0.21484 | 1.0 | 0.59531 | 0.87059 | 1.0254 | 1.3438 | 0.70822 | 0.46446 | 0.75551 | 0.81947 | -0.02431 | -1.40052 | -1.08775 | 10.3465 | 13.15985 | 13.94906 | -0.24258 | 0.48232 | -3.05758 | -3.3357 | 3.5823 |

| 0.024 | 0.27566 | 0.57771 | 0.32941 | 0.04102 | 0.84375 | 93 | 92 | 96 | 0.25806 | 0.37732 | 0.07451 | -0.09961 | -0.21484 | 1.0 | 0.59531 | 0.87059 | 1.0254 | 1.3438 | 0.70822 | 0.46446 | 0.75551 | 0.81947 | -0.02431 | -1.40052 | -1.08775 | 10.3465 | 13.15985 | 13.94906 | -0.24258 | 0.48232 | -3.05758 | -3.3357 | 3.5823 |

| 0.032 | 0.2825 | 0.57283 | 0.07843 | -0.09961 | 1.3184 | 93 | 92 | 96 | 0.25806 | 0.37732 | 0.07451 | -0.09961 | -0.21484 | 1.0 | 0.59531 | 0.87059 | 1.0254 | 1.3438 | 0.70822 | 0.46446 | 0.75551 | 0.81947 | -0.02431 | -1.40052 | -1.08775 | 10.3465 | 13.15985 | 13.94906 | -0.24258 | 0.48232 | -3.05758 | -3.3357 | 3.5823 |

III. Putting the big data on Amazon Web Service¶

During the hackathon, Accenture provided us with a $125 gift certificate to create and Amazon Web Service EC2 instance.

This enabled us to use a p3.2x large instance, putting 1.2Gb into the system. Despite our enhanced processing capability, it was still challenging and time consuming to run all the models. It took approximately 6-10 minutes to run the full models on AWS.

IV. Modelling¶

Multiple attempts using regression techniques were made to model the data. Using resp as our target, our goal was to optimize performance on the metrics of; * R2 score * Mean squared error * Model evaluation time (seconds)

Assumptions that had to be made

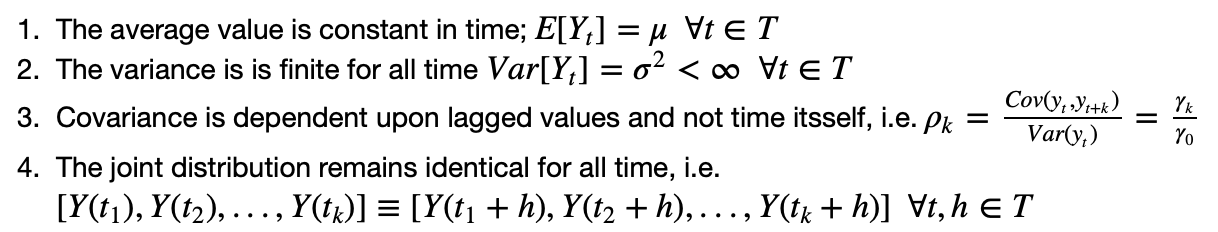

To make a regression analysis on time series data, we had to assume the time series is itself stationary. This means that the value of the feature we're analyzing has an average and variance that is constant in time.

Stated mathematically, the assumptions were;

Are these assumptions valid or realistic? Yes definitiely so. Why? Because the people who were being studied in the original analysis for which the data is being collected were laying down in bed throughout the study. Thus, the there was no stimulus to change in the time series, and it can be assumed to have a constant trend.

Model Development

A function was created to put the data through a pipeline for which it was fitted and scored on several different types of models. The models that were compared were

- Ordinary Least Squares

- Lasso Regression

- Elastic Net Regression

- Ridge regression

- Bayesian Ridge

- K-neighbors regression

- Random Forest Regression

The function that produced this system was this;

import time

import numpy as np

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score,mean_squared_error,mean_absolute_error

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso,Ridge,ElasticNet, BayesianRidge, LinearRegression

from sklearn import neighbors

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

models = {'OLS':LinearRegression(),'ElasticNet':ElasticNet(),

'BayesianRidge':BayesianRidge(),'Lasso':Lasso(),

'Ridge':Ridge(),'KNN':neighbors.KNeighborsRegressor(),

'rff':RandomForestRegressor()}

def model_performance(X,y):

times =[]

keys = []

mean_squared_errors = []

mean_abs_error = []

R2_scores = []

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=10)

for k,v in models.items():

model = v

t0=time.time()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

train_time = time.time()-t0

t1 = time.time()

pred = model.predict(X_test)

predict_time = time.time()-t1

pred = pd.Series(pred)

Time_total = train_time+predict_time

times.append(Time_total)

R2_scores.append(r2_score(y_test,pred))

mean_squared_errors.append(mean_squared_error(y_test,pred))

mean_abs_error.append(mean_absolute_error(y_test,pred))

keys.append(k)

table = pd.DataFrame({'model':keys, 'RMSE':mean_squared_errors,'MAE':mean_abs_error,'R2 score':R2_scores,'time':times})

table['RMSE'] = table['RMSE'].apply(lambda x: np.sqrt(x))

return table

model_performance(X,y)

Best Results

After running this function, we got a table of performance metrics for each model. Note this is when we run on one only one person's data. If we ran on everyone in the study, the metrics were approximately the same.

| model | R2 score | time(s) | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.90017 | 2.85901 | 0.11014 |

| KNN | 0.82439 | 4.02399 | 0.12569 |

| BayesianRidge | 0.53836 | 0.076529 | 0.203805 |

| Ridge | 0.53835 | 0.02263 | 0.20380 |

| OLS | 0.53835 | 0.36989 | 0.20380 |

| ElasticNet | -1.24037e-05 | 0.02514 | 0.29996 |

| Lasso | -1.24037e-05 | 0.02388 | 0.29996 |

Clearly, it was the random forest regressor that achieved the best results.

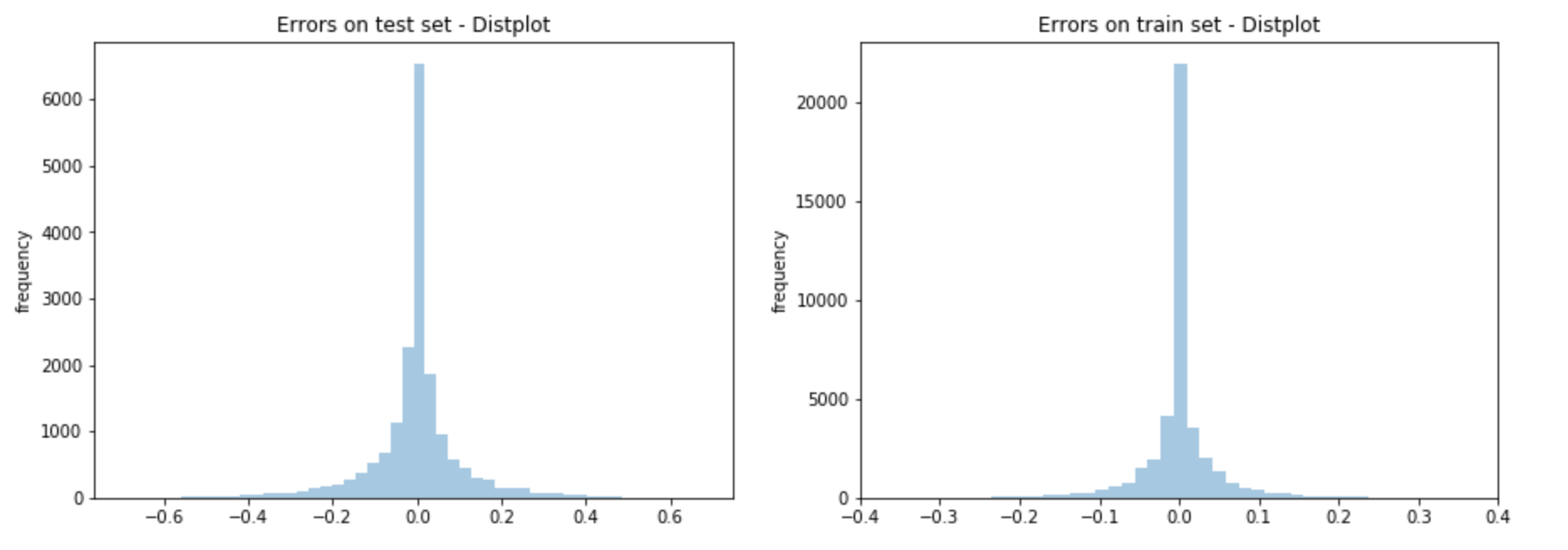

Validating a well fit model

Aside from simply metrics of performance, it's also good to look at how well the model has been fit. Here we see distribution of errors on the train set and the test set;

The frequency count may be slightly different in scale, but this is ok because its size difference is proprotional to the size differences in the train set and the test set.

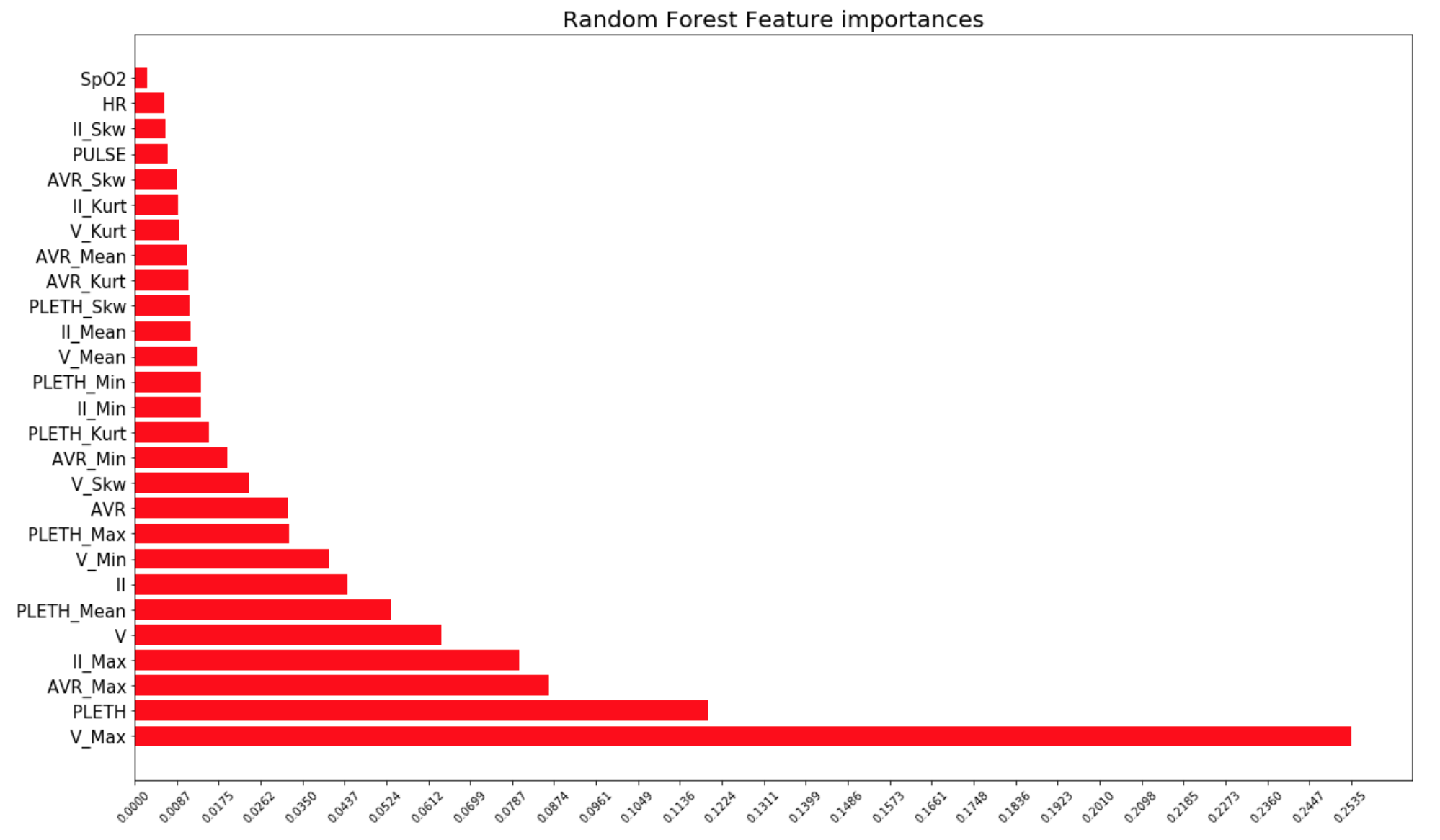

Feature importance

One of the beauties of the random forest package, is it allows us to create an output describing the magnitude of feature importances.

It was also noticed that if we eliminated the plethysmogram data, we could still predict breathing rate with upto about 80% accuracy.

V. Conclusions¶

We can draw a few conclusions. * Using a persons plethysmogram and electrocardiogram data we can predict their respiratory rate with 90% accuracy. * If we train on multiple people's data, we predict anyone's respiratory rate with very good data.

Insights on usage

Being able to predict user's breathing rate with home based wearable technology opens up a lot of opportunities for healthcare. This can allow us to do things such as;

- Have doctors monitor our health at home

- Enhance and assist with continuous health monitoring

- Prevent major health crises before they occur.

Prospects on further usage

Perhaps these algorithms and data collection techniques can be put into smart watch/phone apps. Software could be created that allows for automation of doctor patient interaction, notifying healthcare professionals in real time when a serious issue arises.

Smart watches might save lives one day!

VI. Links to coded notebooks¶

- Downloading and aggregating the data

- Modelling the data

- Random forest performance

- Main github repository

VII. References¶

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrocardiography

- Photoplethysmogram (PPG) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photoplethysmogram#Photoplethysmograph

- Probabilistic Estimation of Respiratory Rate from Wearable Sensors, Pimentel, Charlton, Clifton, Institute of Biomedical Engineering, Oxford University http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~davidc/pubs/springer2015.pdf

- PPG data can be extracted using smart watches: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26737690

- ECG data cen be extracted using smart watches: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/02/the-apple-watch-ekgs-hidden-purpose/573385/

- Clinical data on breathing rates, ppg, and ecg data from ICU patients https://physionet.org/physiobank/database/